Daniela Trucco*

In the past few years, major development strides by the Latin American countries, including some that have been highly positive for young people, have paradoxically coexisted with high indices of violence and insecurity. Unlike the situation in other regions of the world, in Latin America and the Caribbean the countries are at peace, but there are extreme levels of violence within society, to the point that the region has the world’s highest homicide rate. Violence (intentional or not) is the leading cause of death among the population aged between 15 and 50 in Latin America and the Caribbean, affecting particularly men. Seven of the 14 most violent countries in the world are in this region: Belize, the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Jamaica. Between 2000 and 2010, the region’s homicide rate rose 11%, whereas in most other world regions it came down or stood still. The youth population is particularly affected by this context of violence and insecurity.

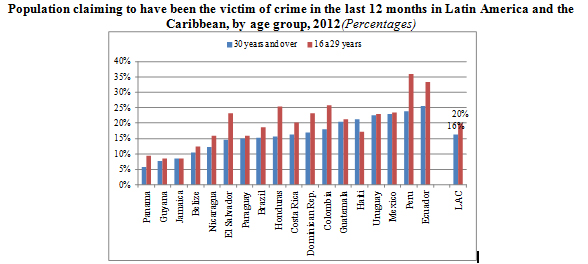

In recent years, Latin America and the Caribbean has gone from a situation of collective violence (in a context of dictatorships and civil wars) to one in which interpersonal violence appears to have been garnering greater prominence in the media and greater attention as a subject of study (Imbusch, Misse and Carrión, 2011, p. 98). Essentially, this attention has focused on the concept of crime, which is hard to define, and the stigmatization of people living in sectors beset by violence. All this matches people’s perception of the contexts of insecurity they face. According to figures gathered by the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP), in 2012 some 20% of young people and 16% of the adult population in the region claimed to have been the victims of some crime (see figure below). The situation varies by country and the youth population is not always disproportionately affected, although it does tend to be more involved where crime is particularly widespread (ECLAC, 2014).

Source: ECLAC based on special tabulations of the biannual survey of the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP), 2012 in: ECLAC, 2014. Note: LAC is the simple average of the results for the 18 countries included in the measurement.

The territorial distribution of violence is uneven, with its manifestations being differentiated particularly in urban areas, where deprived sectors become the setting for violence. Shanty towns and slum areas are characterized not only by poverty but also by violence, and this is a burden that reproduces and exacerbates social exclusion. The stigmatization of youth in these areas for their supposedly violent way of life represents a breakdown in solidarity and a denial of dignity. In these circumstances, the involvement of young people and adolescents, many of them part of the “hard core” of exclusion, in different criminal practices directed by adults, who use them in the service of their own interests in the knowledge that minors cannot be held criminally responsible, has become a matter of growing public concern. Since the 1980s, the gangs operating in cities across the continent have become associated with an expression of youth identity linked to violence, substance abuse and illegal acts such as robbery.

Youth participation in gangs and other organized forms of urban violence has undoubtedly increased and has come about as a direct consequence of marginalization, offering an alternative form of social inclusion (inclusion in exclusion) (ECLAC, 2014). Specialists in youth issues have been arguing for decades that gangs are organizations that provide some Latin American youths with a form of social inclusion: when poverty is widespread, very limited employment options are available and a the State and institutions are near-absent, then the only thing left to give a sense of future to many young people’s lives is their peer group in the barrio. Gangs give them power, a cash income, a space and a feeling of belonging that no other social institution provides (Soto and Trucco, 2015: in Trucco and Ullmann eds, 2015).

This phenomenon cannot be grasped without understanding the sociopolitical and cultural history of each territory in which these organizations emerge. These parameters influence the way they organize, the power criminal organizations have to recruit young people and the type of territorial dominance they exercise. It is important to analyse membership of these groups and the levels of violence that some of their efforts to assert this dominance result in, set as they are within a multiplicity of social processes that facilitate this kind of alternative social inclusion for some of the region’s young people. The literature has identified many risk factors associated with the incorporation of certain sections of youth into violent territorial groups.

Among the risk factors (or enablers) most commonly mentioned in international literature that are more general and can encourage various expressions of violence in youth, we can find the following:

- Growing inequality and exclusion (or exclusions): increasing economic and social polarization and inequality reveal a much more systematic association with levels of violence than poverty.

- Aftermath of civil conflicts: periods of post-war transition associated with a culture of violence in resolving conflicts and greater availability of weapons.

- Drug trafficking: this phenomenon has become the dominant illegal market in cities characterized by violence. Important profit margins can be drawn from this market which in turn defines another set of illegal activities (Perea, 2014). In many of these cities, there is no possibility of competing in the legal market and the alternatives offered by the State in terms of job opportunities for the marginalized young population are even more negligible.

- Migration processes and deportations: the negative effects of migration, mainly international migration, can be fundamental in the life of young migrants, who can face dangerous and violent situations during their journey.

- Domestic violence: one factor associated with violent behaviour is intergenerational transmission of domestic violence, replicating violent response and interaction models in adult life.

- No sense of belonging by youth: understood as lack of adhesion to shared values or recognized forms of participation, lacking a willingness to recognize others with regards perceptions about discrimination or new communicational practices, as well as lack of confidence in social structures and options for the future. All these are important causes behind certain acts of violence.

- Stigmatization of youth: certain youth groups, such as gangs members or young people from vulnerable urban sectors, tend to be stigmatized negatively, reinforcing exclusion processes.

- Institutional disaffiliation: a hostile educational system, added to a labour market that offers few opportunities to many young people also becomes a relevant frustration factor and a facilitator of violent behaviour.

Protection factors that will counteract risk factors in order to mitigate their most severe effects and contribute to a reduction of violence must be carefully identified and analysed in order to create ideal conditions to promote contexts of peaceful coexistence at all levels: family, community and social. Young people´s subjective sense of belonging should be taken into account in the design of these policies.

At the primary level of prevention, the following short and medium term strategies are recommended: strategies to reduce risks such as alcohol consumption or carrying weapons; education and awareness campaigns for the general population, with special emphasis on youth, enabling the promotion of a culture of peace; assessment of violence related legislation in terms of the treatment of violence in youth. The aim is to incorporate or generate guiding or leading elements for the actions of institutions faced with expressions of violence in school and non school environments, using an approach that guarantees rights, with clear regulations and implications for young people that break the law, promoting peaceful ways of resolving conflict.

Secondary prevention focuses on more vulnerable groups that have already been affected by violence; for example, people involved with gangs, that live on the streets or suffer addictions. At this level, it is recommended the improvement in the design and implementation of initiatives that focus on activities such as psychosocial care, support for young people with drug or alcohol addiction problems and demobilisation of young gang members; strengthening strategies to treat violence in schools with protocols that establish roadmaps for care.

Finally, tertiary prevention has a restoration approach which consists of the rehabilitation and social reinsertion of people at odds with the law and that have already committed violence, or in the restoration of damage to victims. At this level it is important to design social policy that promotes criminal liability (sanction), but also social reinsertion through inclusion mechanisms for youth in education and production that considers violence as a significant phenomenon for formal inclusion of those that break the law. Also, strengthening justice systems, opening spaces for reporting and adequate monitoring for both victims and perpetrators. This implies improving the ability of the police to manage reports, as well as improving their investigation tools, processing and actions towards those implicated. There is the need to promote initiatives for youth in conflict with the law; i.e. all those already in jail or detention centres that lack opportunities to be reintegrated to the country’s social, economic and political life upon completion of their sentence. This recognizes a population with rights that requires tools to develop capacities and skills for a decent and productive life once freed.

*Daniela Trucco is the Social Affairs Officer at the Social Development Division of the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), where she works in the areas of education, youth, childhood, and information and communication technologies (ICTs).

References

1. ECLAC (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean) (2014), Social Panorama of Latin America 2014 (LC/G.2635-P), Santiago.

2. Imbusch, Peter, Michel Misse and Fernando Carrión (2011), “Violence research in Latin America and the Caribbean: a literature review”, International Journal of Conflict and Violence, vol. 5, No. 1.

3. Perea Restrepo, C. (2014), “La muerte próxima. Vida y dominaciónen Río de Janeiro y Medellín”, AnálisisPolítico, vol. 27, No. 80.

4. Trucco, D. and H. Ullmann (2015), Youth: realities and challenges for achieving development with equality. ECLAC Books, No 137 (LC/G.2647-P), Santiago, ECLAC.

5. UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime) (2014), Global Study on Homicide 2013: Trends, Contexts, Data, Vienna.